SEEING YOUR FIRST CHILD WITH PANDAS/PANS

Authored by Margo Thienemann, MD and The PANDAS Physicians Network Diagnostics and Therapeutics Committee

PANDAS/PANS: Symptoms. Criteria. Workup. Expectations.

What is PANS?

The term Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) describes the clinical presentation of a subset of pediatric onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). PANS may also be a subset of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).

While the criteria for diagnosing PANS do not specify a trigger, the syndrome is thought to be an immune reaction to one of a number of physiological stressors including Group A Streptococcal infection, Mycoplasma pneumonia infection, influenza, upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, and psychosocial stresses. PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal infections) is a subset of PANS where symptom onset and exacerbations are triggered by Group A Streptococcal infections.

The diagnosis of PANS should be considered whenever symptoms of OCD, eating restrictions or tics start suddenly, and are accompanied by other emotional and behavioral changes, frequent urination, motor abnormalities and/or handwriting changes.

Current Theories

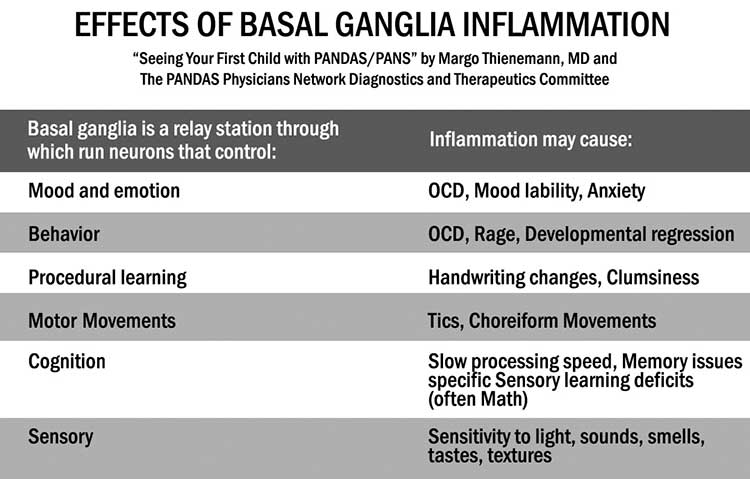

PANS is presently thought to result from dysfunction of the basal ganglia (specifically, the caudate, putamen and globus pallidus). One theory of PANS proposes that serum antibodies cross the blood brain barrier, cross-react with neuronal antigens and dysregulate basal ganglia functions. Another theory suggests that neuroglial immune cells in the brain incite basal ganglia inflammation. Neurons connecting to the basal ganglia affect motor function, emotion, behaviors, procedural learning, cognition and sensory issues (TABLE 1).

PANDAS is thought to be similar in etiology to Sydenham Chorea (a manifestation of acute rheumatic fever). Approximately 30% of Acute Rheumatic Fever (ARF) patients have Sydenham Chorea; of those, about 70% will develop OCD. Like Sydenham Chorea, PANDAS may result from the molecular mimicry of Group A streptococcal bacteria, which stimulates production of antibodies that then cross-react with antigens in the brain, producing a variety of neurologic and psychiatric manifestations.

PANS Diagnostic Criteria

The PANS diagnostic criteria were developed by a consortium of experts and are considered to be a “working draft” that may be changed as more is learned about acute-onset disorders. Current PANS criteria are:

1) Abrupt onset or abrupt recurrence of OCD or Restrictive Eating Disorder

2) Co-morbid neuropsychiatric symptoms (at least 2) with a similarly acute onset: anxiety, sensory amplification or motor abnormalities, behavioral regression, deterioration in school performance, mood disorder, urinary symptoms and/or sleep disturbances

3) Symptoms are not better explained by a known neurologic or medical disorder

Description of PANS Symptoms

1) OCD

It is estimated that 1 – 2% of all children suffer from OCD and about 1/10th of these also meet the specific criteria for PANS.

Traditional OCD presents with mild obsessions and compulsions that become more involved and burdensome over time. In traditional OCD, symptoms tend to be persistent with minor variance in symptoms (often referred to as a waxing and waning). In contrast, PANS OCD presents with a sudden onset typically from mild or no symptoms to debilitating in an abrupt amount of time. Often, parents recall the exact date of symptom onset, and frequently report “it just came on out of the blue.”

Diagnosing OCD in children can be complex because compulsions may resemble oppositional behaviors when children become upset and act out when their compulsions are thwarted. Many compulsions are either mental rituals (and therefore difficult to observe) or appear as extremes of an acceptable behavior (e.g., compulsive handwashing). Common OCD rituals in children include: washing/grooming, checking (locks, door), counting, ordering/symmetry, hoarding, restrictive eating, and repetitive questioning. To qualify for a diagnosis of OCD, tools such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Checklist and Scale (CY-BOCS) are used to determine the impact the compulsions/obsessions have on daily life.

Emerging research suggests different treatment options are available for children with PANS OCD than for children with non-PANS OCD. Understanding the difference between the two forms of OCD allows appropriate interventions to be implemented.

2) Eating Restriction

PANS children describe various reasons for not eating normally or adequately, such as: fear of vomiting, sensitivity to taste, smell, and texture, fear food is spoiled, or fear of being poisoned. In some cases, the restricted eating is directly related to body image distortions, including concerns about being overweight (even when the child is normal weight and was previously satisfied with their body habitus.)

3) Anxiety

Anxiety frequently presents as constant, generalized anxiety or age-inappropriate separation anxiety.

4) Sensory Amplification

PANS children may become uncharacteristically and intensely bothered by smells, tastes, sounds, and textures, causing difficulties with daily routines, such as brushing teeth, riding in a car, eating, and dressing.

5) Motor Abnormalities

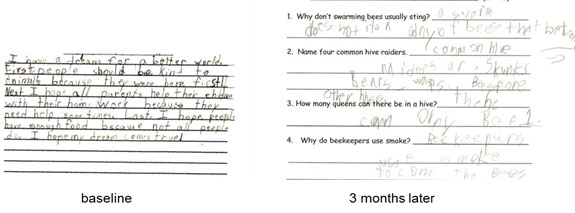

PANS children may exhibit motor and vocal tics, handwriting changes and/or clumsiness.

6) Behavioral Regression

PANS children may display regressed behaviors, such as: baby talk, refusal to carry out age-appropriate grooming activities, tantrums, clinginess, and/or separation anxiety.

7) Deterioration in School Performance

Psychological testing of children with PANDAS, a subset of PANS where strep is the infectious trigger, has found impairments on a visual-spatial recall test, on measures of executive function, and on a dexterity test. PANS children may also experience a decreased processing speed, memory issues, and/or difficulty in math and calculation.

8) Mood Disorder

Depression, mania, irritability, hypersexuality, emotional lability, and rage have been noted during a PANS exacerbation. Moods may change from happy to sad to angry in moments. Reactive rage (as oppose to predatory rage) may start instantaneously and stop as quickly, leaving the child remorseful and confused.

9) Urinary Symptoms

An initial complaint may be urinary frequency. A careful history will often expose additional symptoms. PANS children may develop polyuria (up to many times per hour), frequent urges to urinate, and/or day and night secondary enuresis. These urinary symptoms are not due to UTI, anxiety or OCD type worries.

10) Sleep Disturbances

Polysomnography has demonstrated a variety of sleep abnormalities in children with PANS, including initial and middle insomnia, REM behavior disorder, parasomnias, and/or sleep phase shifting.

PANS Workup

When evaluating a child for PANS: 1) Evaluate for Group A streptococcal infection. 2) Rule out acute rheumatic fever (echocardiography may be helpful) 3) Check for other infections. 4) Exclude non-infectious triggers. 5) Refer parents to a specialist.

Recommendations for Detailed Workup

1) Evaluate for Group A Streptococcal (GAS) Infection

Inquire about recent exposures to streptococcal infections, and symptoms of GAS infection (sore throat, headaches, and abdominal pain), rashes, and perianal itching. If inappropriate to office situation, refer to primary care provider for the following exam and specimen collection. Examine and vigorously swab throat and nose. Examine skin for a scarlatina or perianal rash. If symptoms and physical exam suggests, swab perianal and vaginal areas.

If rapid strep test is negative, the swab should be sent for a 48-72 hours GAS culture. Perianal culture orders should indicate that evidence of strep is sought. If the clinical encounter is within 2 weeks of symptom onset, check for rising antibody titers (ASO, Anti-DNAse B) by obtaining an initial set of titers and the repeating in 4 – 6 weeks. Since elevated titers are the norm in grade-school aged children, anti-streptococcal titers are only helpful when a two-fold rise in titers is observed.

Group A streptococcal infections are contagious and often spread back and forth among family members. If GAS is found in the child with PANS, it may also be appropriate to obtain strep cultures of close family members. This may decrease the risk for subsequent GAS infections in the PANS child.

There is good evidence from acute rheumatic fever that sudden onset OCD symptoms can result from otherwise asymptomatic GAS infections. PANS children do not always present with “classic strep throat” despite colonization and infection. Getting an adequate throat swab is highly dependent on the practitioner vigorously swabbing on tonsils and posterior oropharynx. Some GAS culture positive children (> 37% in one study) do not demonstrate elevated titers with ASO and Anti-DNAse B even when perfectly timed. This reinforces the need for relevant lab testing, checking for symptoms of prior untreated GAS infection, and examining skin.

2) Rule out acute rheumatic fever (ARF)

Careful auscultation for a murmur should be done for every child. If the child has a history of polymigratory joint complaints, frank chorea, erythema nodosum or erythema migrans, it is imperative that the child be evaluated by a pediatric cardiologist to exclude rheumatic carditis.¹

3) Check for other infections

Evaluate for other infections as indicated by the history and physical. Check mycoplasma IgM for active mycoplasma infection. IgG is not particularly helpful. Mycoplasma pneumonia titers are less accurate than Mycoplasma PCR. Recurrence of PANS symptoms may also be precipitated by viral illnesses.

If urinary symptoms are present, obtain a urinalysis. In PANS, this is likely to be negative and suggest that the urinary urgency, frequency or secondary enuresis are manifestations of PANS, rather than a urinary tract infection.If the child has been on antibiotic therapy, check for Candida Albicans as it can exacerbate symptoms.

4) Exclude non-infectious triggers

Non-infectious triggers may include such things as drug ingestion and poisoning by heavy metals or other environmental toxins.

5) Refer parent to specialist

Refer parents to pediatric psychologist and other appropriate specialists (Cardiology, Rheumatology, Immunology, Neurology, Sleep, Otolaryngology, and/or Infectious Disease).

Parental Influences and Setting Expectations

When faced with the acute impairments that characterize PANS, parents and caregivers will search for answers from both reliable and unreliable sources. Educating the parents and caregivers about the clinical presentation, course of illness and prognosis of PANS will help the child at school and home. It is important to set realistic expectations.

Medical and Longer-Term Expectations

1) PANS OCD has a relapsing remitting course. Most children will experience at least one recurrence of symptom onset due to a PANS trigger. Parents need to understand there is no “quick fix”.

2) Traditional OCD is characterized by a waxing and waning course with modest changes in severity. However, with PANS OCD, the course is relapsing-remitting, with dramatic, abrupt exacerbations of OCD and ancillary PANS symptoms. One study shows changes of 17 pts on CYBOCS scale.

3) Unlike traditional OCD, some studies have shown improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with PANDAS after 2–6 weeks of antibiotic treatment. It is unclear if these improvements are from treatment of a latent infection or from some other non-microbial effects.²

4) Residual OCD may persist despite any treatment of infection, inflammation, CBT, or medications. In the 1999 study using aggressive immunomodulatory treatment, patients improved on average 45%. Cognitive-behavior therapy (specifically exposure with response prevention) can be helpful in eradicating symptoms of PANS. Anti-obsessional medications can also be used in combination with CBT but studies indicate to “start low and go slow.”

Home and School Expectations

1) PANS OCD is OCD. Family education and support is critical, particularly in the early stages of illness. Providing material on treating and managing childhood OCD is an important step.

2) Communication with the school will help alleviate stress and establish a better understanding between faculty and student. Parents may request to be informed of documented strep within the classroom and ensure that teachers are following good hygiene practices. Clinicians and parents might also volunteer to provide an informative lecture to class, parents, and teachers, and/or request a 504 Plan, IEP, or SST.

¹ Gewitz MH, Baltimore RS, Tani LY, et al. Revision of the Jones Criteria for the Diagnosis of Acute Rheumatic Fever in the Era of Doppler Echocardiography Circulation May 19, 2015 vol. 131 no. 20 1806-1818.

² Obregon D, Parker-Athill EC, Tan, J, et al. Psychotropic effects of antimicrobials and immune modulation by psychotropics: implications for neuroimmune disorders. Neuropsychiatry (London). Neuropsychiatry (London). 2012 Aug; 2(4): 331–343.